The staccato

thunk, thunk of a microphone interrupts musings and cuts across the

conversations of two hundred, maybe two hundred fifty people. “Could you all take your seats?” a laconic

voice intones. “It’s time, folks.” The crowd moves unhurriedly to the podium-end

of a hall musty with the smell of antiques up for auction.

It is a beautiful morning in May, 1994, one of the first fine

days of a spring that has been dawdling for months, but there I am, Nancy Grossman, neglecting

my garden and my guests to attend another auction. I claim the folding chair on the aisle that

I’ve reserved with a jacket. My husband

John sits down beside me. He’s circled

several items in the catalog. I’ve only

jotted one lot number on the back of my bidding card.

Since 1991, I had been settling into my seat at auctions with all the earnest hope of a believer easing into a pew on Sunday morning. We had opened a bed and breakfast from scratch, in 1992, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. We furnished it almost entirely from our eccentric gleanings collected through long hours of tedium and patently unhealthy food, peppered with those exciting, short bursts of adrenalin that only an auction can supply. The basic needs – the beds, the dressers, the chairs and rugs, the lamps, the twenty end and night tables – were amassed during an initial six months of auctions, three, four, sometimes more, a week. After all that, you might think we’d never want to hear the crack of a gavel again. Quite to the contrary: auctions are one of those mutated meta-viruses for which there is no cure.

φ

I pride myself on having

an eye for the unusual, and our B&B is huge, a six bedroom Georgian

Colonial once owned by a governor of New Hampshire, a bottomless pit that

voraciously swallows up all the artwork and bric-a-brac we can bring to

it. There is always room for more, so

that, even when the essentials had been found, the trips to auctions don’t

stop. Our needs are no longer so

obvious; now it is time to inject character and whimsy. And so, much more for the fun of it, we trek

an hour, an hour and a half, through wind and rain, snow and slush, to see what

we can find. Our B&B is located in

southern New Hampshire. We don’t bother

with the upscale auctions of Boston. We

most often head north.

Today, internet auctions have become ubiquitous, but in 1991, the concept of the virtual auction had yet to elbow its way into our collective unconscious. Beyond the obvious, the thrill of “winning” an auction, be it on-line or off, a virtual auction with its round-the-clock access, the isolation and anonymity of the solitary bidder, the effortless place-your-order nature of browsing via search engine, has about as much in common with the real McCoy as a 120-acre flea market in the parking lot of a football stadium does with thirty folding tables set up by the side of the road in rural Maine.

Most auctions in northern New England are held on weeknights, starting at six. With luck and a fast auctioneer, they may end by ten. Previews for a six o’clock auction will start at three; the bulk of the audience drifts in by five. The crowd will fall into roughly four categories. First, city dealers, the vendors of pedigreed antiques to the wealthy of Boston’s Back Bay, in their three-piece suits and Italian loafers. Sprawled next to them, or more often ranged around the walls, are the grizzled country dealers who sell “junk” out of their barns to “them fool tourists.” They’ll favor Woolrich and boots they bought from L.L. Bean long before Bean put out its first catalog. The “retail” folks, the shoppers, come hoping to pick up something trendy, an old jelly cupboard or a Stickley rocker, for a steal. The rest, mostly locals, come to marvel at how people spend their money. They provide the lyrics for the Greek chorus: “Lordy, I hauled me a boxload of them things down to the dump just last month, only ol’ Willie there, he wouldn’t let me leave ’em.” They’ll tell you that auctions make for wicked good entertainment of a winter’s night.

The auction this spring day isn’t our usual hour’s drive – it is right here in my hometown, ten minutes door to door. An upscale affair, it’s being staged in the town’s swankest catering hall and comes complete with a sixty-four page, four-color catalog. The auctioneer wears a tie. Nor is this our usual fare, your basic, generic antique auction. This sale is billed as an auction of “Ephemera, Postcards, Exonumia & Selected Items of Americana.” “Exonumia” I have to look up; it has to do with money, minted items, coins and medals. “Ephemera,” on the other hand, is easy. Think of the airy adjective “ephemeral” – short-lived, transient, fragile, fleeting. I’m here today for the ephemera.

Ephemera, to a collector, is paper. I’ve had a passion for paper for years. Ledger sheets from long dead businesses in the fine hand of long dead bookkeepers. Candy boxes containing bundles of letters held together with seventy-five-year-old satin ribbon. Cartons of Ladies Home Journals from the ’40s, sheet music with evocative illustrations on the front page, funnies from the Boston Globe, circa 1930, which remind you that “funny” is a subjective construct of generation and culture. It’s paper, that most perishable detritus of civilization, that brings us eyeball to eyeball, mind to mind, with the daily lives of other people in other times. I’ll never get enough of it.

φ

We arrive an hour early

to preview the pure potential of a room filled with anywhere from three to five

hundred items. “Select items,” the

flyers always boast. “From the estate

of.” “Fresh to market.” “As is, where is.” A horde of potential buyers peer through

magnifying glasses and jewelers’ loupes, consult guides and scribble notes to

themselves as they assess the authenticity and worth of the more obviously

valuable goods displayed. Then they get

down to the serious work of rifling through books, burrowing to the bottom of

boxes, crawling under the tables, in quest of that odd item the auctioneer, his

staff, and the rest of the crowd may somehow have missed. If anything, it’s this dream of buried

treasure that’s at the root of my auction addiction. I edge my way into the midst of all these

industrious hunter/gatherers, then settle into the methodical inspection of

items that catch my fancy. For me, this

morning, it isn’t the select items of Americana, though they are supposedly why

we’d come. It certainly isn’t the

exonumia. For me, it’s the ephemera.

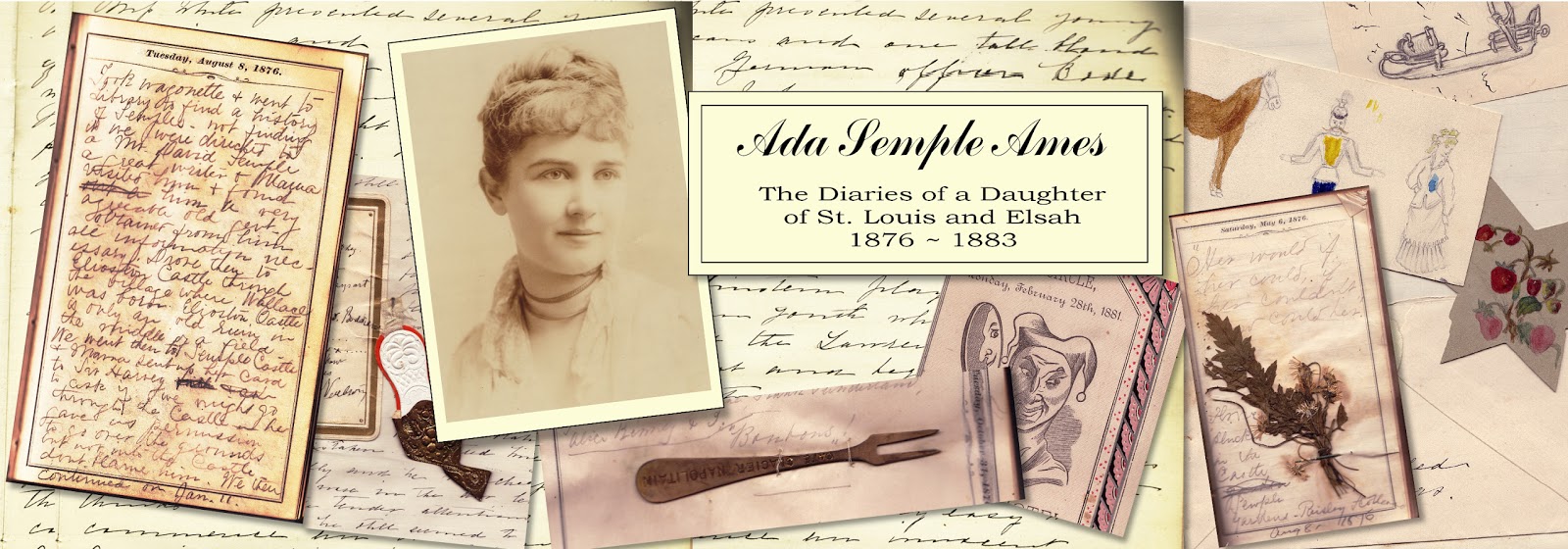

Only one bundle of paper puts out a foot to trip me up this particular day, a hodgepodge of nine slim, dog-eared notebooks that have been tossed into a small, square cardboard box and labeled as “Lot #324.” Pushing a few things aside, I make space to inspect the contents of the box: eight diaries, one autograph book, a passport, a tiny pocket notebook and a few loose odds and ends. Very little of the text is legible, not because of fading or poor condition, but because of difficult handwriting. What little of it I can decipher strikes me as exceedingly beautiful prose; phrases pieced together read rather like Jane Austen. Several of the diaries have envelopes pasted to their pages, with letters inside, in French and German, as well as English. The smallest of the diaries has 118-year-old flowers pinned to its pages. I know at once that I want to take that little box home with me.

Such a strange way to shop! In a hall without price tags or guarantees, you decide what you consider an item’s “worth” – and then you compete to buy it. A good auctioneer will move ninety items an hour.

“Okay, ladies and gentlemen, Lot #1,” he announces as the first of his runners steps forward, holding high a trayful of buttons. “Lot #1, one hundred forty Australian pinback buttons, the commemoratives from Down Under.” The auctioneer reaches over to the tray, picks a few at random and reads them to his audience. “You saw them – Navy Day, Red Triangle Day, YMCA, Wattle Day. Where are we going to start the pinback buttons? Who’ll give me three hundred to get things going today?” And within forty seconds, the gavel comes down on a sale of $325. I suddenly wonder how much those diaries are going to fetch, when the time comes.

Swiftly, methodically, in numerical order, the auctioneer makes his way through his wares. Stamps, badges, tokens, photos, calling cards, trade cards, playing cards and postcards, valentines, catalogs, signs, receipts and billheads, books and board games. Few lots have to be passed for want of a buyer. My husband’s success in obtaining an early edition of Gibson girl drawings at a good price makes him amenable to waiting out my chance on the box I covet. We both know that I can ask a runner to bring the diaries up early, out of order, a practice ordinarily allowed after the first hour. But we both subscribe to the theory that, if at all possible, it’s always better to wait. Let the audience spend up all its money.

And so, finally, a runner steps forward, a big, meaty fellow with my little box in one hand and five of the diaries, my diaries, fanned in the other like a winning poker hand.

“Lot 342, ladies and gentlemen, the box of nice early Semple Ames diaries. What do I hear? Do we have, what, a couple three hundred dollars to start it along? How about a seventy-five dollar bill, set this thing into the bidding?” I moan inwardly. Hold on. “Fifty? How about twenty-five to get this thing going?” My arm flies up. “Twenty-five, I have twenty-five. Hands all over the house at twenty-five, do I have fifty? Fifty, do I have seventy-five?” My hand shoots up again. A pause as the auctioneer looks for a hundred. I start to hope. “Okay, eighty-five, I’ll take eighty-five. Ninety-five. I have eighty-five, do I have ninety-five? Do I have ninety-five?” My hand bolts upward again. “Ninety-five! Ninety-five, do I have a hundred, a hundred dollar bill?” Where is this going? “Ninety-five, do I have a hundred, a hundred, it’s still cheap.” I fling my hand up again. I’m so good at this! “Hold on to your money, little lady, you’re my ninety-five, who’s my hundred?” I am mortified. He gets his hundred. I go to one-ten. Someone else inches it up to one-fifteen. At one-twenty, I hear, “Are we all in and all done at one-twenty?” A pause. I don’t breathe. “Sold to the little lady!”

Little lady? Who’s he calling a little lady?

φ

Several days pass before I can find time to delve into my little box. On close inspection, five of the diaries appear to be the writings of one woman whose name I can’t make out at all, dating from 1876. Marion Turner of St. Louis, Mo., had written her name in one on September 8, 1900, in a neat and childish hand, and two more, from 1911 and 1917, had once belonged to another Turner. The passport was issued to a bespectacled gentleman, one Joseph Lumaghi, born October 6, 1860, in Collinsville, Illinois, height 5 feet 10 inches, hair gray, eyes brown; no distinguishing marks or features. I put the diaries back in the box in order by date: 1876, 1879, 1880, 1881, 1883, 1900, 1911, 1917. They are fragile and full of loose papers.

Running a bed and breakfast does not lend itself, in the high season, to quiet perusal of diaries. It isn’t until the end of foliage season, six months later, that I am able to bring my carton out again. I sit down by the fire with a cup of tea and the first diary, the 1876 volume. “The Centennial Diary,” it reads on its first page. The next several pages of this book provide useful information to the diarist: eclipses for 1876 (four, two of the Sun and two of the Moon); the time of sunrise, sunset and high water, and facts from history for each day of the month, each month of the year (Battle of Pea Ridge, 1862, on Monday, March 6; French Revolution, 1830, on July 29, a Saturday); interest tables and a page on The Interest Laws of the States; postal rates, both foreign and domestic (on all letters throughout the United States, 3 cents for each half ounce or fraction thereof); presidential facts; principal cities, their distance from New York by miles and hours, and population, 1870. St. Louis, population of 310,869, it informs me, lies 1089 miles, or 45 hours, from New York. The population figure has been edited in ink, raising the figure to 400,000. Today, St. Louis has a population of two and a half million.

With persistence, I manage to work out the first page of entries. It reads, in pencil, “My darling Lily, before you read this diary I want to ask you once more and impress upon you never to mention any thing in this book. It is between you & me – I turn this down so you will see it surely. I know you would not say anything about it.” I notice a fold mark where the page was once, indeed, turned down. It is no longer.

Attempting to read these pages is maddening work; transcribing them is the only answer. Once transcribed, I can sit back and enjoy the writing, and thus, page by page, I come to know the author, it turns out, of seven of my volumes. My new acquaintance: Ada Semple Ames, of St. Louis, Missouri, who becomes the wife of one Henry Turner, and the mother of the child, Marion. By the middle of the first diary, I go shopping for a small, fireproof safe. These little books are starting to feel like a treasure – and a responsibility.

I am no historian, and it has been a long time since I last pursued anything remotely scholarly. But once I come to know Ada, the mind, I want to learn everything I can about the world that created that mind. I want to understand the archaic references, find all the places named and follow in this woman’s footsteps. Thus begins a journey of discovery, finding out just who this woman was, while learning the ropes of research on the fly. The good news is that Ada came from wealth. It is far easier to research the well-to-do than the poor.

φ

I want you to make Ada’s acquaintance as I did, in her own words, but, first, I will provide you with the little bit of information I stumbled on, almost by accident, during the almost two years I spent transcribing. Ada, the eldest child of Edgar and Lucy Semple Ames, I discovered, was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on March 3, 1861. Edgar, a prosperous early resident of St. Louis, along with his brother Henry, presided over the family meat packaging business; both can be found in The Compendium of American Genealogy, as can Ada’s maternal grandfather and one of her brothers. Edgar died in 1867, when Ada was only six. Lucy Ames, Ada’s mother and a woman of wealth and business acumen in her own right, took control of her husband’s business enterprises as well as the raising and education of her four children, Ada, Henry, Mary, known as Mamie, and Edgar. In July of 1876, Lucy crossed the Atlantic with her children to further their education in the capitals of Europe. More about Ada later. You already know far more than I did when I set out on this journey.

Just a few words on the culture within which Ada grew up. The few words? Propriety. Passion. Manners. Across socio-economic boundaries, Victorian women aspired to be “ladies,” men to be “gentlemen.” Women were said to have a civilizing influence on society in general and men in particular. “What woman wills will be accomplished,” John Ruskin wrote. Linda S. Lichter, in her recent book Simple Social Graces, paints a picture of Victorian children raised to “develop the trinity of a social conscience – civility, duty and self-control.”

Nothing could be more evident as we join Ada in her day-to-day life. Reading her words, the Victorian worldview floats evocatively into focus. This was a time in which a mother brought her daughters into society with her, educating them in manners and poise while making their daily social rounds. Decorum, confidence, bearing, wit, all were well polished on the afternoon tea circuit of cities like St. Louis. In the circles within which Ada was raised, etiquette and grace came under the public scrutiny of the grandest of St. Louis society’s grandes dames.

In the midst of these most proper times, girlhood friendships became the point of convergence of repressed passion. Closely chaperoned at all times, Victorian young ladies clung almost amorously to their dearest chums. Today’s reader may find it surprising to come upon descriptions of such adoring intimacy, possessiveness and jealousy – between girlfriends. However, it is equally clear that, as with girls of any era, members of the opposite sex were a chief preoccupation; in Victorian times, flirtation was one of many art forms a well-bred young lady was expected to master.

The “Lily” to whom the diary is addressed represents just such a girlhood passion. Lily appears to have been a schoolmate of Ada’s, perhaps at a boarding school that Ada no longer attends. Ada will also refer to her as “Geraldine,” “Geraldini” and “Dini.” Tucked in the back of that first diary is a card which read: “If this book is ever found by anyone will he or she please send it to Ada Semple Ames, care John Munroe, Banker, Paris, France.” On the back of this card, in pencil, is a name and address: Miss Ste. – and the last name is illegible. The address is 78 Madison Avenue, New York City, Etats Unis d’Amerique [the United States of America]. In the diary, Ada speaks of going to Lily’s house, at 78 Madison Avenue. The address, a boarding house in 1876, is a dead end.

φ

Editorial

notes: Ada's diary and journal entries will be rendered in italics. Any sections of my own, like the Introduction above, will be in standard type. All parentheses are Ada’s; my own parenthetic thoughts are

bracketed. I have left Ada’s grammar,

punctuation and spelling precisely as I found it and as best I could decipher

it, making changes to more modern usages only if absolutely necessary to

clarify meaning. All foreign phrases are

rendered as Ada wrote them; translations follow in brackets. ~ Nancy Grossman

Now, start reading Ada's diaries and journals, starting with the earliest date and moving forward. In this case, you are looking for January 1876 (under July 2013).

Now, start reading Ada's diaries and journals, starting with the earliest date and moving forward. In this case, you are looking for January 1876 (under July 2013).

Wow! I was running today and got lost exploring and ended up in Elistoun. It's still as gorgeous as it must have been not quite a century and a half ago. I saw a little sign that Principia college had posted saying Elistoun Arberetum. It had a little faded sepia picture of a young lady and her dogs (did Ada have dogs?) on the front lawn of the victorian. I was at once quite in love with the mystery of the old teal Victorian. I had to know more about the owner! Thank you for how much you have discovered about Ada, and thanks for sharing it.

ReplyDeleteHi Samantha - that most probably would have been Ada's daughter Marion, quite a character in her own right! Read on through the diaries and eventually we will get to some from Ada's later years, trying to adjust to automobiles and her daughter's wild ways! Are you at school at Principia? Nancy

ReplyDelete